TRIESTE, DECEMBER 1918, OPERATION PURGE: REMOVING THE “BAD” ITALIANS

“Trieste, city out of history: out of history because its characters testify the plurinational history of Mitteleuropa, while its name express nothing but nationalistic obsession”.

Claus Gatterer, scholar (translation of a quote from book “L’identità cancellata” – “Cancelled identity” by Paolo G. Parovel)

On November 3rd, 1918, as Italian troops entered the city, Trieste lost her freedom.

After 536 years of happy union to Austria (to which the city devoted itself in 1382), which turned it from a fishermen village to one of the main ports of the Monarchy and of the Mediterranean, Trieste, pearl of the Adriatic, was occupied by the Italian army.

For three years, during World War I, the city had been one of the main targets of the Italian Army, which bombed it (LINK) and ferocious battles, all lost to the firm Austrian-Hungarian defenders of the city, who stopped the enemies in front of Mt. Hermada and ultimately crashed it with the victory of Caporetto, driving the Italians behind the Piave and saving the harmless citizens from the nightmare of bombs: LINK

Only the end of a war that the Central Powers fought, for four years, against the overwhelming men and means of the Countries of the Entente, followed by the implosion of the Empire, allowed Italy to gain entrance to Trieste and occupy it as a spoil of war.

And a new nightmare became real in Trieste, it was the harsh repression of the Italian Royal Army and its hunt for “pro Austrians”: which, in a multicultural port city that had been in an union with the Austrian Crown for more than half a millennium, meant persecuting all inhabitants.

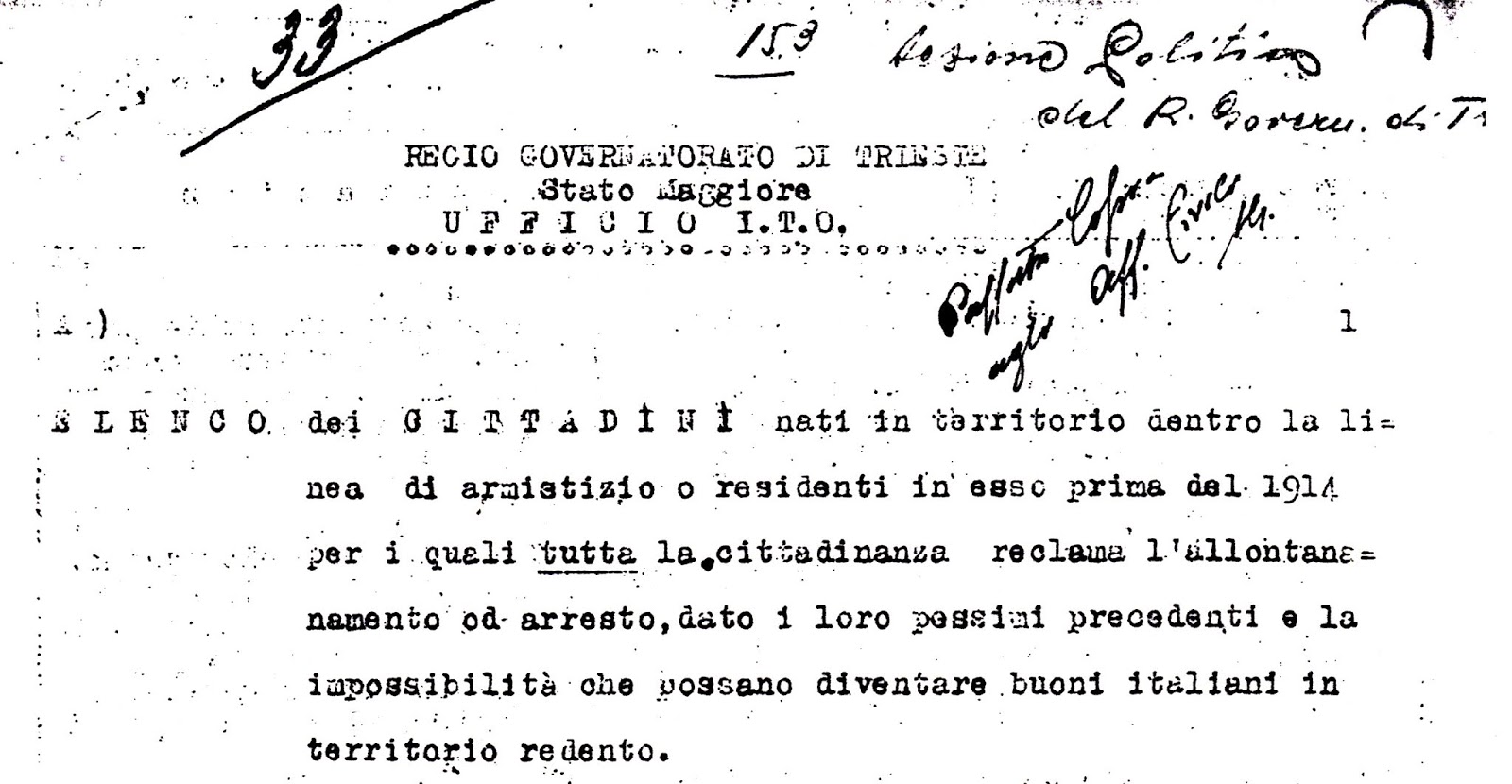

The duty to enforce this first ethnic cleansing was entrusted to the special office I.T.O. (Ufficio Informazioni Truppe Operanti – Servizio I dell’Esercito, the Information Office of Operative Troops – Service I of the Army) of the Royal Government in Venezia Giulia which, as early as in December 1918, issued the first proscription list.

This first list, dated December 1st, 1918, was a list of citizens “born in the territory within the armistice line, or residing thereof before 1914, whom all citizens demand be expelled or arrested given their extremely bad past and the impossibility for them to become good Italian in the redeemed territory” (it is the text on the image above). This is the text of the measure condemning to civil death hundreds of citizens regarded as pro-Austrians and whose only misconduct was being loyal to their Country: the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy.

In the Urbs Fidelissima, Austria’s most loyal city, it was normal being faithful to the Habsbourg Monarchy, and the I.T.O. regarded it as “disloyalty” to the occupying Italy of the Savoia: in Trieste, the wide majority of the people had served in the Austrian-Hungarian armies, fightingfiercely on all fronts of the War, including the one opened in 1915 with the Kingdom of Italy; the very few “irredentisti” who deserted were an exception. This is why the modus operandi of the I.T.O. was to select its victims to set an example for all the people that the Italians were trying to submit by force.

This is why the first targets were the patriotic organizations of the Austrian citizens, as well as public officers who had duly served their Country.

The I.T.O. stroke Riccardo Colledani, Rodolfo Stark, Guglielmo Dabiani, Enrico Kunstel, Augusto Pelszeghi, Romano Saris, Guglielmo Todeschini, Francesco Schnorr, Adolfo Mosettig, and Carlo Mosettig labeling them as follows:

“leaders of the gangs that devastated and ransacked the properties of Italians on 23 May 1915. Instigating spies, offenders of all that is Italian. Accusers of employees of Italian sentiment”.

They were some of the many citizens who, as Italy declared war to its Austrian-Hungarian ally, protested against the Italian betrayal as well as setting on fire Il Piccolo, the newspaper of the irredentisti.

Rodolfo De Struppi, Augusto Proft, Carlo Furlan, Carlo Meclanuch, Marcello Cuschian, Enrico Cergnigei, Augusto Cegnar, Michele Mrecch, Otto Klenovar, Antonio Verdier, instead, were accused to be:

“Well-known leaders of the Lega Patriottica della Gioventù Triestina, fierce organization of the Austriacanti in Trieste”. (Austriacante/i is a derogatory way to refer to pro-Austrians, sometimes translated as “Austriacants”).

The purge did also cut the heads of the local police: Arturo Sterling, Francesco Ghersina, Antonio Paolettich, Rinaldo Kurzemann, Giuseppe Mlekus, il capitano Horatceck, Carlo Tomadin, all defined as:

“Old police tools. Ferocious torturers of the Italians”.

And the revenge of the Italians did not even spare those who had showed, with too much enthusiasm, their attachment to Austria, their own Motherland.

Among many there is Giuseppe Domines, owner of the buffet in Via San Nicolò 11, considered “guilty” of being the second to climb the Giuseppe Verdi monument (in Piazza San Giovanni) end to have disfigured it.

Instead, Rodolfo Schuckar and Francesco Schneider were accused of being “Germanics, provokers who offended in the most disgusting way and at any given chance all the Italians they could find”.

Angelo Crivicic, Catterina Vucetic, Father Antonio Vascotto, Augusto Stecher, Davide Horn and his wife, Ignazio Mlaner, were charged with “accusing many people of high treason, resulting in their deportation of imprisonment”.

Pasquale Malvasia, owner of the pub in via Punta del Forno, downgraded on paper to a “postribolo” (brothel), was labeled as “extremely dangerous subject, vile spy of the police, well-known by all good Italians”.

Then there were the “mangiaitaliani” (Italian-eaters); among them there were bank employee Giuseppe Mattijevic (most angry Italian-eater, Croatian, vile spy of the police), Professor Giuseppe Brumat (Italian-eater, denouncer of many students who ended up arrested and deported) and the “terrible Italian-eater”, officer of the reserve of the Austrian navy, Edmondo Kasseger.

And then there were Giovanni Pizz and Ernesto Giosento, for they “recognized and denounced the volontario irredento Cirillo, sentenced to death and then pardoned”, Giuseppe Magazzin owner of the “Fogli volanti Triestini”, satirical newspaper: “which, with immoral words, insulted the King, the Army, and the Poeple of Italy”, the “man from Roiano”, Nicolò Tossutti, Italian citizen deported for “having requested and obtained the status of Austrian subject, joining the army to fight against Italy” and Stefano Vucetic, who “recognized and denounced Nazario Sauro”.

After this first wave of persecutions, the actions of the I.T.O. extended to the rest of the Austrian Littoral, renamed “Venezia Giulia”. On 23 December 1918, lists A and C are released. List A (covering the districts of Capodistria – Koper, Lussinpiccolo – Mali Lošinj, Sesana – Sežana, Gorizia – Gorica) included “citizens whom all inhabitant demand be expelled given their extremely bad past and in view of the impossibility for them to become good Italian in the redeemed territory (it is suggested they be deported)”.

Reading the rushed motivation for the removal from civil society of those people there are good reasons to shiver and to feel ashamed. Because those suggesting such measures presented themselves as “liberators” from tyranny, but in truth they were ruthless occupants who were establishing an extremely racist dictatorial regime in a land where all folks had lived in peace for centuries in the shade of the equal, well-organized, and tolerant Austrian government.

The proposed deportation of citizens that, according to the I.T.O. could not become “good Italians” were once again based on a summary “accusation” that left no room for defense to the targets, for it depended solely on their loyalty to Austria, to the States they were still citizens of.

Which were the allegations? It was enough being a teacher, like Orel di Corte d’Isola (near Capodistria – Koper) who had been too much pro-Austrian in educating his pupils. Or being a Priest too loyal to the Double Monarchy as was Father Nardnic, Parrish Priest of Corte d’Isola (Korte), who was accused of being one of the “former Austrian spied”.

The same goes for Father Francesco Persic from Vrh, labeled as: “fanatic and troublesome anti-Italian agitator. One month ago, the postal censorship presented a postcard in which he manifested sentiments against the new regime”.

Or for Francesco Volarich, judge in Pinguente (Buzet), regarded as not trustable for expressing in subversive terms against the Italian troops that were entering the city and therefore promptly labeled as “inciting fanatic” and leader of the subversive Yugoslav party.

Engineer Renato Penso, from Gorizia, is portrayed as “ferocious hater of the Italians” and former Austrian spy, while Lucrezia Platzer, herself from Gorizia, was labeled as:

“Austrian spy who remained in Gorizia after our troops left, regardless of the orders of the commanding officer, General Cattaneo, provided the Austrian army with information about the organization of the Italian army and accused citizens of Gorizia of helping the enemy, thus causing them severe damages and persecutions at the expenses of Italian citizens”.

Antoni Radlosivc, also known ad Matezevic, farmer from Unie – Unije was labeled as “Austrian spy” (without further explanations).

Medved, judge in Sesana – Sežana was himself a “dangerous agitators” and former Austrian spy: “His behavior towards Italian officers shows the incompatibility of his presence in Venezia Giulia”.

Darinka Deglic from Neresine (Nerezine) was guilty of being the wife of a former policeman, a pensioned teacher, she was labeled as a dangerous agitator against Italy.

And of course, Gorizia was itself subject to the repression of the Austrian public security forces, and so Augusto Bregant, Luigi Krapez, Carlo Grilanc, Giuseppe Rojec, Andrea Cehovin, Pietro Brisko, Edoardo Kosmina, Francesco Furlan, Francesco Saksida, Martino Duagar, Pietro Bressan, Antonio Krecic, and Andrea Paulin were deported.

Those included in list C were luckier: they are the “citizens who were not born in the occupied territory or not residing thereof before 1914, whom shall be deported outside the armistice line”.

They were the Austrian citizens that had reached Trieste during the war, and the I.T.O. proposed they be sent away. Among them, Simeone Pils from Unterchaid (Bohemia), resided in Muggia and judged “of irreducible anti-Italian, pro-German sentiment”.

This is the main accusation against all Austrian citizens, regardless of their ethnic group: they are “anti-Italians” for daring to fight against Italy which, on 24 May 1915, attacked its own ally at a time when its engagement on the Russian front was extremely harsh.

Follows the list of the “citizens born in the territory within the armistice line and residing therein before 1914 which require strict surveillance”.

This “strict surveillance” can lead to exile, as happened to Francesco Rizzi from Muggia, and the main targets are those who are defined “pro-Yugoslavia agitators” and “subversive”. It is the grounds for the aggression to Yugoslavia, one of the new States established after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary.

But this is only the beginning of the violent, nationalistic persecution of Italians, the professed intention being to cancel from the “redeemed” Trieste any trace and memory of Austria and of its plurinational past.

This violence hit thousands of harmless civilians, who had to surrender to the rules of the new “regime” that, unfortunately, was tolerated by the international community.

In 1919 started the forced italianization of names and toponyms (including caves, taken away from Austrian associations to be placed under the control of new, Italian speleological groups: LINK) and it continued until 1945. One more step in the ethnic cleansing and removal of the identity of the subjugated people.

No “good Italian” could have a foreign name, and without an Italian name it was impossible keeping a job. This is how Trieste lost its soul, its history, sacrificed on the altar of the most ruthless nationalism of what was to become one of the harshest dictatorships in Europe.

Because, soon, Fascism added its own violence and persecutions against Slovenes, and then came the Italian racial laws against the Jews (LINK). Finally, it all culminated in World War II and its horrors, including the Italian aggression of Yugoslavia, in an attempt to get rid of the hated Slavs (LINK).

The “true” liberation of Trieste from the nationalistic Italy, from Fascism, and from the Nazi regime did not happen until May 1945. And the new freedom was brought by the Yugoslav partisans that Italians and Germans labeled as “criminals” who, in truth, were part of a regular army, as well as the children of those soldiers who had fought in the Austrian army during WWI, protecting Trieste, the multiethnic “jewel” of a plurinational Country, from the Italian aggression.

The first Italian proscription lists issued in December 1918 against the citizens of the Austrian Littoral: Link to the original document, in Italian

Translated from blog “Ambiente e Legalità” – “Environment and Legality” by Roberto Giurastante