At the outbreak of the World War, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire fought on many fronts, including the sea. The main duty of the Imperial and Royal War Navy (Kaiserliche und Königliche Kriegsmarine / K.u.K. Kriegsmarine) was to maintain control of the Adriatic sea, as fleet in being. For the Empire, the Adriatic was a vital source of supplies, an exclusive interest zone, although shared with the unreliable Italian ally, and with the port of Trieste, in the upper North, as main port.

As early as in August 1914, at the beginning of the war, the K.uK. Kriegsmarine had to face a fare difficult situation, having to stand against the greater forces of the Entente. The navies of France and of the United Kingdom, thanks to a wide numerical superiority to the Imperial and Royal War Navy, did immediately enact the Otranto Barrage. An outright encirclement, identical to that against Germany in the Northern seas, in order to cause the economic collapse of the powerful Central Empires.

Despite being unable to in against the joint feeds of France and of the United Kingdom to break through the Otranto Barrage, because even in case of success, this would have only driven the fleet from its bases to open Mediterranean, in search of an improbable ultimate battle with the powerful opponents (for example, like the Battle of Jutland in the Northern Sea, fought by the Royal Navy against the Kaiserliche Marine), the K.u.K Kriegsmarine was perfectly capable of defending its own maritime routes and to have complete control over the Adriatic.

This was clear when the Entente’s fleet tried to attack the opponents right in their headquarter, which means pushing the Barrage right in front of the Empire’s own commercial and military ports, in order to stop any maritime activity even in its territorial waters, therefore preventing the very movement of freight, rough materials, and passengers.

On the other side, the result of this strategy depended on the involvement of massive forces, and its preliminary test was the Entente’s operation to break Austria’s Barrage against Montenegro, which had joined the war with Serbia and with the Entente, which ended with an unequal naval battle – nine French and British war ships against two Austrian – Hungarian ships – resulting in the sinking of cruiser SMS Zenta.

The Entente, after the powerful reaction of the K.u.K Kriegsmarine, after a few raids against the military bases in Kotor and Dalmatia, withdrew to the Otranto Barrage. A key role in fighting back the Entente’s attacks in the Adriatic is that played by submarines.

Underwater warfare was the greatest innovation of maritime war, and World War I served as its very testing ground. At the beginning of the war, the K.u.K Kriegsmarine had only 7 submarines involved in underwater warfare, as it was waiting for the new units commissioned to Germany (the Country that at the time, as proven by the very results of maritime warfare, had developed the construction of submarines the most).

Regardless to the limited number of unites, the K.u.K Kriegsmarine, together with the German allies, of which would adopt also the strategies, adapting them to its own battlefield, trained very well-prepared crews. And the greta knowledge of the coasts and seabed of Eastern Adriatic contributed to make Austrian-Hungarian submarines unrivalled, despite having less resources than their enemies. A weapon, submarines, made to attack and entrusted to the hands of young and well-trained officers with much fighting spirit.

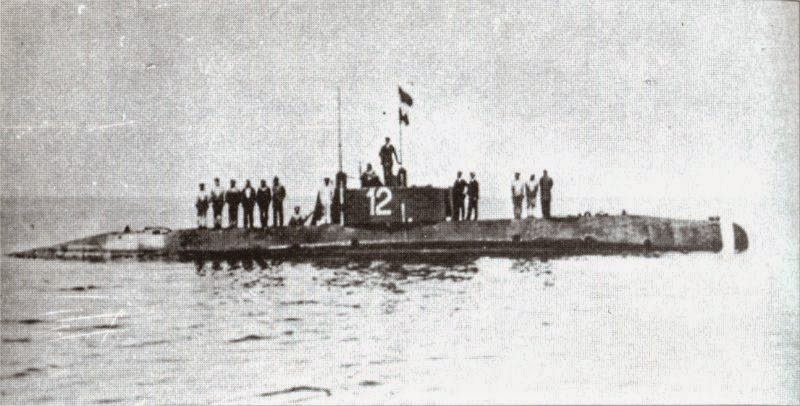

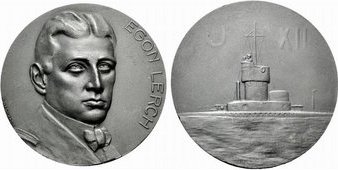

Among them, Linienschiffsleutnant (Ship-of-the-line lieutenant) Egon Lerch, 28-year-old, born in Trieste, in command of submarine SM U-12, displacing 250 tons. built in the Whitehead shipyard, in Fiume.

This was an improved version of SM U 5-6 units, but its deck was still weak. The main problems were its limited autonomy of immersion, at a limited depth (30 meters), of unsealed batteries that would fill it with sulfuric acid vapors when recharged and, least but not last, the possibility to have only two torpedoes ready in the Kaiserliche und Königliche Kriegsmarine.

It was with such groundbreaking boats, and in the wait for the new vessels ordered from the German ally, that the K.u.K Kriegsmarine entered the war and had to face the powerful enemy fleets.

Still, the technical shortages of what then were only experimental instruments were balanced by the iron will of men tempered by the spirit of Admiral Tegetthoff. And with no doubt, Lerch was one of the greatest examples of that fighting spirit. Breaking through limits, attacking when it seemed impossible, never giving up: only some of the characteristics that made lieutenant Lerch the most praised submariner of the K.u.K Kriegsmarine.

In facts, he was the person who archived one of the greatest successes of the K.u.K Kriegsmarine. On December 20th, 1914 the U-12 at Lerch’s command left la base di Šibenik to the Otranto Channel to attack the French fleet that participated in the Barrage.

On December 21st, at 6.30AM, 20 miles from the Sazane Island, it engaged fight with the enemy, and Lerch orders a crash dive. The U-12 reaches periscopic depth and approaches enemy naval units. This means most of the French fleet, during naval maneuver. Sixteen big units, including some battleships: one submarine against a whole fleet.

At 8.30 the U-12 is 800 meters from the French fleet, and Lerch decides to attack the flagship, approaching to 600 meters and launching two torpedo in a row, the first to the forward part of the battleship, the second to the middle.

The U-12 submerged to 20 meters depth to avoid the reaction of the enemy. The first torpedo hit battleship Jean Bart to the bow, near the collision bulkhead, the second missed the stern by 50 meters. French admiral de Laperyèrewas, Commander in chief of the French fleet, was on Jean Bart and, as he did not believe submarines could travel that far away from their bases, had no arranged a naval escort for the battleships.

Following the event, the Jean Bart, seriously damaged and inclined by bow, reached Malta to be fixed, and thus remained out of battle for months. The U-12, having reached its operational limit, had to return to its base, unable to perform a second attack.

This action proved decisive: after their flagship was hit, the French retrieve their fleet from the Adriatic. On December 22nd, the U-12 reached the naval base in Kotor, acclaimed but showing clear marks after the harsh battle: the crew was exhausted due to the terrible exposure to the mix of sulfuric acid vapors and discharge of diesel motors, the craft was ruined, and electric batteries dried out. It was urgent substituting them.

On December 28th, the U-12 and its crew reached the main naval base of the K.u.K. Kriegsmarine, Pula, for official celebrations. The Emperor himself congratulated Lerch and awarded him the Order of Leopold Knight Cross and a Military Merit Medal. In total, the U-12 crew received 13 Military Merit Medals (3 gold, 10 silver).

It represented the peak of success for the Austrian hero of submarine warfare, who then may expected would be also awarded the most prestigious medal of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire: the Knights’ Cross of the Order of Maria Theresia.

Yet, Admiral Haus opposed to Lerch, and this became an insurmountable obstacle: he blamed Lerch for not performing a second attack with torpedo against the French fleet after hitting the Jean Bart.

Lerch’s decision was understandable: in that situation, setting any more torpedo for launch was impossible, and the state of batteries allowed no other maneuver but leaving the battlefield for a safe place, and to finally emerge as soon as possible to prevent the crew being intoxicated.

However, it is possible that the heads of the Marine disliked Lerch also for different reasons: he was the official lover of Archduchess Elisabeth Marie, the exuberant, favorite granddaughter of Emperor Franz Joseph, daughter of Crown Prince Rudolf of Habsburg, who committed suicide in Mayerling. Archduchess “Erzsi” (as her grandfather called her) was married at the time and, even if she lived separated from her husband, her liaison with the young Marine officer caused great embarrassment for the Imperial Court of Vienna.

After victory in Sazan, Lerch’s U-12 patrolled Southern Adriatic and distinguished itself in many actions, but without any important success.

On the other side, it is important taking note that all surface vessels of the main fleets of the Entente had left the Adriatic, considering it impossible dealing with the threaten of Austrian submarines:

“… it is no longer possible carrying out actions in Montenegro’s ports, but it is also impossible thinking of continuing any kind of action in the Adriatic, without taking great risks” (declaration of admiral de Laperyère, Commander-in-chief of the French fleet in Mediterranean to the Ministry of Marine after the battleship Jean Bart is hit by the torpedo of the U-12).

Still, new clouds were appearing on the horizon. Italy was about to enter war side by side with the Entente. The U-12 served in North Adriatic: first in Pula, then in Trieste. It was time to prepare for the attacks of the disloyal former Italian ally. The Gulf of Trieste was about to turn into the field of a new maritime war. This is how Egon Lerch returned to his Trieste, which he left for what would be his last mission.

But, before that, something else happened, darkening his “splendor”. On May 28th, at 9PM, the U-12 engaged battle and sank Greek steamer Virginia near Piran (now in Slovenia). 22 people lost their lives, only two survived. Greece was a neutral State and this attack, officially a mistake, created many difficulties to Austrian-Hungarian diplomacy.

The war with Italy had started from just a few days, and Lerch mistook the Greek steamer with an Italian cruiser. Was it possible that such an expert commander had committed this gross mistake? The official version was that the Greek vessel struck a mine. It was important covering the hero and preventing a diplomatic crisis.

Sure, it is not easy judging decisions taken in harsh war conditions. During the early days of the conflict with Italy, the Austrians expected Italian reckless operations, including the landing of shock troops in Istria or other such resounding actions.

It is highly probable that the Evidenzbureau informed military commandos in the area about it, including the navy. This would make Lerch’s mistake the effect of a general alert of the services. Still, the truth was never revealed, no investigations would follow: the U-12 was about to become itself part of history, together with its whole crew.

On August 7th, 1915 at noon, the U-12 left Trieste for a new mission: attacking the Venice shipyard, the main port of the Italian Royal Army (Regia Marina) in Northern Adriatic. There were many battleships, cruisers, fighters and torpedo craft anchored in Venice.

After the U-26 submarine sunk armored cruised Amalfi on July 7th, only 15 miles from Chioggia, Italian had extended and modified the position of mines in front of Venice, as well as prohibiting main units from leaving. So, to catch the enemy it was necessary entering the well-protected port of Venice avoiding its many defenses.

Lerch’s plan was ambitious: lurking, underwater, in front of the barriers that protected the lagoon of Venice and then follow the first Italian ship that would get in it, reach the roadstead where armored cruises were, launching the torpedoes, reverse the direction and leave before the enemy’s torpedo boats could block access to the canal.

A really reckless plan, considering that the submarine should have completed this maneuver in shallow water, and an autonomy that did not exceed three hours. 180 minutes to blow a deadly hit to the hated Italian enemies, the “traitors”.

August 8th, afternoon: the chance is right there. An Italian destroyer returns to the port of Venice, and Lerch can follow it. Bit the U-12 was entering a deadly trap. Traveling under water, it could not avoid hitting one of the new torpedo mines of barrier G, placed by Italian right in front of the access to the port.

8 August 1915, 4.30PM, the Venetian lagoon: a violent explosion under water and a very high water column. It was the end of the U-12 submarine, of its commander Egon Lerch and of the whole crew.

On January 3rd, 1917, the Italian navy retrieved the U-12’s remains: they had sank at 20 meters depth. Ever since, the crew members rest in the Isola di San Michele cemetery.

Dare beyond any limit, attack no matter what, never give up: this was the fighting spirit of commander Egon Lerch, Trieste’s forgotten hero.

Translated from blog “Ambiente e Legalità” – “Environment and Legality” by Roberto Giurastante